Abstract:

Robotic micromanipulation technology developed in the last three decades has greatly facilitated research in cell engineering, and fully automated cell manipulation systems are accordingly demanded. Aiming at the adherent cell injection for high-throughput screening, this research proposal is meant to explore novel robotic cell micromanipulation and injection methods. The research background and current status are firstly presented. Then the literature review on cell microinjection and involved key technologies are investigated from two aspects of microscopic computer vision and micro-robotic control. Finally, with the ambition of building a perfect robotic microinjection system for adherent cells, the system architecture and major equipment required for experiments are outlined, system procedures are listed step by step, some improvements are proposed, and expected outcomes are correspondingly planned as well.

1. Background

Different from robotic control of macroscopic objects, research on microscopic objects in electronics, biology, medicine, and other fields, such as cell fusion, DNA injection, chromosome transplantation, and other technologies, all require micromanipulation systems. With the help of the micromanipulation equipment, the tasks of grabbing, holding, transferring, assembling, and injecting objects with the characteristic size of micron and submicron can be precisely completed [1]. As the basic technology of cell engineering, cell manipulation is one of the most important applications of micromanipulation. Traditional cell manipulation relies on the operation of skilled operators, which is inefficient. However, in the past three decades, the automated cell manipulation system formed by the combination of micro-robotic control technology and microscopic computer vision has gradually developed and evolved [2]. This advance not only improves work efficiency but also provides better platforms for cell engineering research related to microinjection, nuclear transfer, embryo transfer, and so on. For example, robotic cell manipulation has greatly promoted the development and application of high-throughput screening technology [3], which makes it possible to process hundreds and thousands of cells per experiment rapidly and accurately.

Given that disorders of intercellular communication are responsible for diseases such as cardiac arrhythmias, cancer, etc., by measuring the intercellular communication and then screening the drug libraries, the optimal treatment for these diseases can be identified. And a standard technique for this is to inject fluorescent molecules into cells and then to monitor their transferring among other adjacent cells [4], [5]. In this context, a fully automated adherent cell injection system for high-throughput drug screening is badly needed, which is exactly the goal of [a new project] led by Department of Mechanical Engineering in the City University of Hong Kong. Though a lot of efforts have been put into automating cell manipulation, there are still large gaps to fill.

For one thing, the majority of the existing research provided effective solutions for the automated manipulation of single cells [6]–[8]. However, they mainly focused on the manipulation of large suspended cells [9], fewer robotic systems were developed for the manipulation of adherent cells, which exist on a culturing surface in most mammalian tissues and have highly irregular morphology, smaller size and thin thickness, making the cell recognition and injection challenging [10], [11]. For another, most existing robotic manipulation systems for adherent cells suffered from a low degree of automation, which are either manually operated via joysticks, or involve complex hardware and experiment procedures, impeding their large-scale implementation. Furthermore, in light of the sprouting up of machine learning and intelligent control technologies in the past few decades [12], more intelligent automated cell manipulation methods should be explored to improve the performances of conventional systems, like the more speedy and accurate recognition, position, and injection.

In summary, it is of great significance to explore novel robotic cell micromanipulation and injection methods. And my ultimate objective is to build a fully automated system for high-throughput microinjection of adherent cells.

2. Literature Review

As mentioned above, the automated micromanipulation system is built based on microscopic computer vision and micro-robotic control technology. Therefore, the literature review on cell microinjection is investigated from these two aspects.

2.1 Microscopic computer vision

Without the inclusion of any additional sensors, all information about the cell manipulation process is obtained by the microscopic vision system, which means that computer vision is the basis of automatic cell injection tasks. Through the image capture and processing, it is supposed to achieve the following functions: 1) To search, identify, locate the target cells, and then keep tracking during the platform movement, providing the real-time position of the target cells in the field of vision for the motion control subsystem; 2) To complete detection work involved in the operation process, including detection of the morphology and structural patterning of cells, detection and locating of end-effector tips, detection of contact surfaces, etc [13].

It is evident that the key technologies mainly fall on target detection, recognition, and tracking. And there are some common hurdles in microscopy imaging, like under high magnification, a small vision region makes targets easy out of the field of view, the low-contrast make it difficult to focus the target and to measure deep information, etc. Fortunately, the development of machine vision has been relatively mature, it would be feasible to select appropriate image processing methods according to specific demands. For example, literature [14] employed a motion history image algorithm and an active contour model to detect the end-effector tip. And in literature [15], two vision-based algorithms named the Gaussian convolution model and histogram-based thresholding method are used to detect the contact of micropipette tip with dish substrate and cell top surface. Besides these traditional methods, Machine Learning has been widely applied in image recognition and machine vision, like the popular Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [16], [17].

2.2 Micro-robotic control

Based on visual feedback, a variety of automated operations can be achieved through different actuators and corresponding controllers.

(1) Firstly, the raw cell or cell cluster samples should be preprocessed before injection, that is, to control their position and structural patterning in 2D or 3D space. Because cells with orderly patterns provide good environmental conditions for subsequent visual recognition and localization, which can guarantee the survival rate of cells after injection. Traditional cell aspirating and holding controlled by a manipulator can not work for the high-throughput concern [18], [19]. And the most promising ways to control cells’ movements are field-driven technologies, such as magnetic, optical, acoustic, or fluidic fields, which use field generators to generate desired forces to manipulate the cell’s position and shape [1]. Compared with other fields, the acoustic field formed by sound waves is advantageous in swarm control because the acoustic wave has multiple pressure nodes to trap the objects and it can produce larger manipulation forces, which has important applications for cell manipulation. For example, literature [20] firstly used surface acoustic waves (SAWs) devices as acoustic tweezers to pattern fluorescent beads and cells. literature [21] developed a tunable patterning technique by generating tunable standing SAWs fields and succeeded in arranging microparticles into reconfigurable patterns in microfluidic channels.

(2) Motion control is the key part of automatic cell injection, including a). the position or tracking control in X-Y directions actuated by the motorized stage, b). the height and angle control of end-effectors in the Z direction actuated by a robotic manipulator, c). the injection volume control actuated by a robotic microinjector, etc [10], [15]. These tasks are accomplished directly by precise actuator components, and all require high control accuracy and no overshoot. And the general control strategy used in most existing research is visual servoing based PID algorithm [22], [23], which is practical enough but too rough to meet optimal performance requirements. So it is worth trying to draw on other advanced macro-robotic control theories and practices.

(3) Traditional single-cell injection systems don’t take into account injection path planning, which is necessary for the batch cell injection situation. In the case of high-throughput multi-cell injection, an optimal injection path need to be planned among multiple targets, considering the shortest travel length, less diversion, etc. In literature [10], the classical traveling salesman algorithm was employed to generate the shortest path for the batch injection of ten cells, but it depended on the human to provide deposition destinations. Moreover, to avoid the needless intervention of human operators, it is recommended to integrate pattern recognition of cells into the system.

3. Methodology

As mentioned in the introduction part, a micro-robotic system for high-throughput screening should be developed to automatically inject fluorescent dye into adherent cells. Therefore, according to the existing work and new requirements, the system architecture and procedures are designed, major equipment required for experiments is listed and some novel methods are proposed as follows.

3.1 System Architecture and equipment

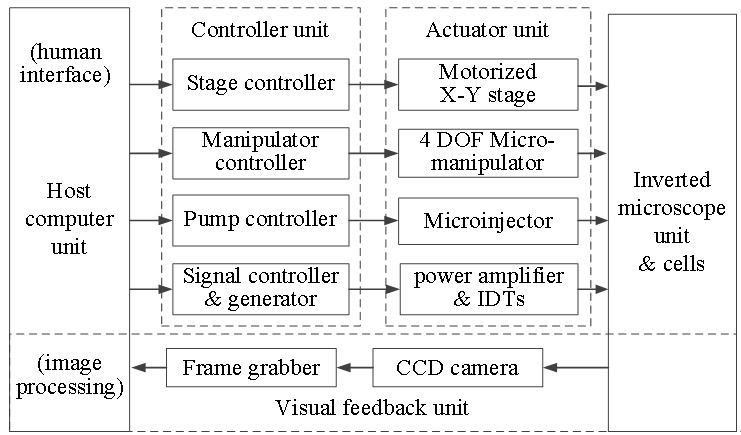

As shown in Fig.1, the designed micro-robotic system adopts a typical architecture of the microscopic vision-based computer control system, which consists of several units like microscope unit, actuator unit, controller unit, visual feedback unit, and host computer unit. And the major required hardware devices in each unit are all listed, including a standard inverted microscope, a motorized X-Y translational stage, a 4 DOF DC-driven micromanipulator, a CCD camera connected to the microscope, a Microinjector with glass micropipette, interdigital transducers (IDTs) to generate acoustic waves, a host computer to process image and provide human interfaces, etc. Besides the aforementioned instruments, a custom-built software system should be developed to integrate and schedule all the functions.

3.2 Procedures and methods

The whole automated injection task can be divided into the following several sequential steps: 1) the structural patterning of adherent cells; 2) the detection and selection of adherent cells; 3) the reconstruction of the 3D cell morphology based on cell’s 2D shape and height to determine the injection location and injection volume [13]; 4) the execution of cell injection: move the micropipette tip to cell, penetrate the cell membrane, deposit the specified volume of materials and retract out of the cell; 5) the switchover between different cells and cell segments according to designed path. Furthermore, these steps fall into two categories: step 2,3 are mainly achieved by machine vision algorithms running on the host computer, and step 1,4,5 are more of robotic control technology, which interact with the underlying hardware. Since there is already some existing work as described in the Literature Review part, methods for improvement or new demands are partially proposed.

First of all, for step 1, it is more advisable to use surface acoustic waves (SAWs) to pattern adherent cells. Different from conventional applications on microparticle manipulation that SAWs are formed in an open-loop manner, the visual feedback can be integrated into this cell patterning system to constitute a close-loop pattern control system, in which SAWs virtually act as actuators. This idea has been roughly tested in the newest report [24], where breast cancer cells are controlled to move along designed trajectories. Besides the manipulation of rotation and transportation of single cells, the controlled multiple cell patterning is worth trying. To achieve this goal, precise pattern recognition should be firstly conducted based on machine learning methods.

In addition, for motion control of the injection, though the PID control algorithm that used in almost all existing work can get decent results, some problems have to be considered for better control performance. For one, the parameters of the PID controller can be troublesome to tune without accurate system models, and there is always a trade-off between dynamic and steady performance, which means the high accuracy and rapid response cannot be achieved at the same time. For another, a fixed controller cannot adapt to different systems and situations. In view of that the cell injection process described in steps 4 and 5 is a repetitive task under similar conditions for each operation, Iterative Learning Control (ILC), an intelligent control strategy used in industry automation [25], [26], can be added into the original feedback control system. Like a feedforward term, ILC exploits control input and error information of former operation to adjust the control input of present operation, which can achieve high accuracy after several iterations and robustly reject uncertain disturbance caused by different cell types or cell morphologies.

4. Outcomes and value

Since robotic micromanipulation is a relatively young field, the novel robotic cell micromanipulation and injection methods deserve every effort of study and are promising for valuable outputs. During the completion of this fully automated adherent cell injection system, a set of sophisticated hardware and software systems will be developed, and key technologies described above will be tackled, which can be reported and get good paper publications. Moreover, the success of this new project would be able to build theoretical and experimental foundations for the next generation of micro-robotic cell manipulation technology with minimized human intervention and increased system throughput, which can be promoted to broader practical applications in clinical work.

For the Reference section and other details, please visit RP_zyk-micromanipulation to find a complete version!